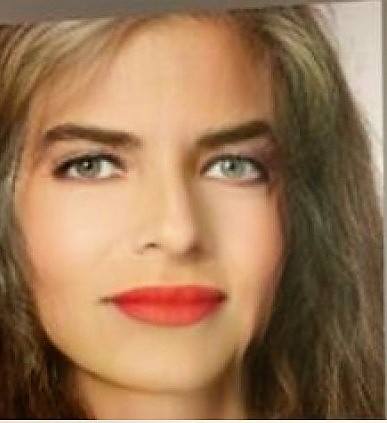

Maltese Theresa Zammit Lupi at the University of Graz, Austria

Maltese Theresa Zammit Lupi with a Phd in the conservation of manuscripts from London, has made a cutting-edge discovery while working at the Special Collections of the University Library at the University of Graz, Austria.

The discovery was made during her work while she was inspecting a fragment originally found in 1902 in El Hibba, Egypt. Theresa Zammit Lupi’s has discovered that codices of papyrus, with bindings running through the centrefold, existed as far back as 260 BC. Dating back to times pre Christ, this could be the oldest book in the world. The fragment was first part of a notebook, and includes legible Greek text describing beer and oil taxes. It was later recycled as wrapping for a mummy.

Oldest known papyrus book 250 BC

While this is a preliminary dating, the oldest book is a great archaeological, and historical evidence found to be some 400 years older than what was previously thought to be the earliest sample with evidence of stitching in book form.

Read more

Phoenician of Ancient Europe

The origins of cuneiform may be traced back approximately to the end of the 4000 BC. At that time the Sumerian carved pictographic tablets in Uruk (Erech), for example, the picture of a hand came to stand for both Sumerian šu that is “hand” and also for the phonetic š. As in Chinese, Sumerian words were largely monosyllabic, so for example, ba, bá, bà, ba would have different meaning. but often representing similar concepts - sun, day, bright...

Ancient Mediterranean Map Major Cities

They used clay tablets - being pressed into the soft clay with the normal order of signs - columns running downward changing to from left to right, without any word dividers. This change of writing methods made some signs change from one side to the other.

The system was adopted by the Akkadians, who established themselves in Mesopotamia 3000 BC. Babylon was an ancient city located on the lower Euphrates river in southern Mesopotamia, within modern day Iraq. Babylon functioned as the main cultural and political centre of the Akkadian speaking region of Babylonia.

Read more

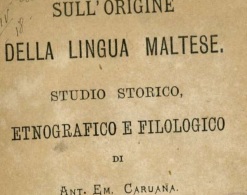

Researching Lingua Maltese Studio Storico Etnografico e Filolgico

Antonio Annetto Caruana (1830 – 1905), also known as A. A. Caruana, was a Maltese archaeologist and author

University of Malta Rector, Librarian and Keeper of Antiquities at the National Library of Malta, Director of Education in Malta's imperial administration, Caruana is best known for his activities as an archaeologist, has published numerous books and articles. He worked on the excavation of the Hagar Qim neolithic temple complex.

Lingua Maltese Studio Storico Etnografico e Filolgico by Caruana published in 1896

This brings me to a book I am researching at the moment published in Malta, in 1896, in Italian with the title “Lingua Maltese, Studio Storico, Etnografico e Filologico” by Em. Caruana, given to me by my dear neighbor friend as his most precious antique purchased as a rare item in Italy.

Lingua Maltese by Caruana published in 1896

Many of the ideas of this noble Maltese man have since been challenged, yet we find ourselves returning to them listening more closely to his story of Ancient Greeks in Malta. According to Caruana, all the Greek “Copto”-s that spoke Ionic Greek dialect are Slavic languages. The famous Rosetta Stone inscription is in 3 languages has also been written in the Ionic dialect. Ancient Egypt Rosetta Stone

Today we know that within the region, a more than a few educated souls were Greeks, for they even had Schools * (of Athens), some were Roman, sent out to the foreign lands to govern their provinces, we also find some Slavs, we know them by their names.

The region was "Roman”, that meant 10% of taxes on all goods, plus the legal benefits for carrying a Roman Name, for only a few could have called themselves “Romans”. Do you remember, that was the time of Caligula and Ceasar, mad-men convinced of their divinity, killing millions of villagers, while on their conquests.

The people of the region that called itself " Macedon” aparenlly spoke a language different to Ancient Greek but had scholars that were fluent in Greek and Egyptian.

Decree of the Maltese with greek inscription 200 BC bronze from Malta - Epigraphic Collection of Archaeological Museum in Naples

Originally carved in Ionic Ancient Greek, now it is known by its Latin translations where the letters are not so profoundly expressed as symbols and frequencies,or music!!!

Translation of the Ancient Greek Maltese Napoli Decree 200 BC

Lingua Maltese, Studio Storico, Etnografico e Filologico” by Em. Caruana

The precious book from the 19th century, within its pages contains a study of the history of Malta during the time of Greeks for around 400 years, from 600 BC to 200 BC. The Maltese islands were somehow inside the cultural or commercial sphere of the Mycenaean civilization. Lycophron's brief reference to the settlement in Malta of a group of Greeks who, after the siege of Troy - 1250 BC were prevented by the gods from reaching their homelands.

The author refers to the time as the Golden era when democracy was introduced to the island that has already advanced in writing skills, received from Phoenicians. The identification of Gozo, with the Homeric island of Calypso is not a modern 'invention' but goes back to 300 BC.

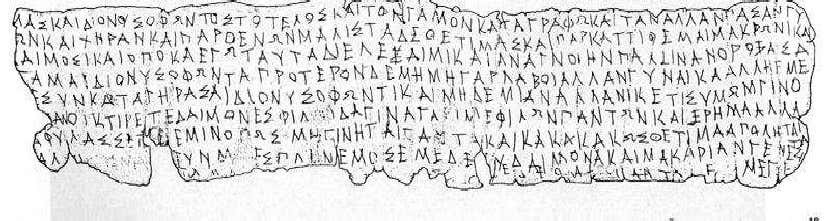

Pella Tablet in Doric Greek in Macedonia 450 BC

The Pella curse tablet is a text written in a distinct Doric Greek idiom, found in Pella, the ancient capital of Macedon, in 1986.

Inscribed on a lead scroll, it is now dated to the first half of the 400 BC. The Pella curse tablet has been forwarded as argument that the Ancient Macedonian language was a dialect of North-Western Greek. Some, however, argue that the region spoke Ionic or Jonic (ć).

At 400 BC this is how an ancient love letter / curse was written by an obviously rich and totally spoiled youth who perhaps had Dionysophon and Thetima as her servents. Translated by Dr. James L. O'Neil (2006) says -

"I forbid by writing the ceremony and the marriage of Dionysophon and Thetima, and of all other women, and widows and virgins, but especially Thetima. And I assign them to Makron and the daimones. And whenever I shall unroll and read this again, after digging it up, then Dionysophon may marry, but not before. Mayhe not take any wife but me, and may I and no other woman grow old with Dionysophon. I am your suppliant; pity me, dear daimones, for I am weak and bereft of all friends. But protect me so this does not happen and evil Thetima will perish evilly, [undecipherable] mine, but may I be fortunate and blessed,"

The Dionysus cult was one of the region's “stay happy” and sing while praying...

Greeks and Macedonians, an Ancient Debate

Pre-Hellenistic Greek writers expressed an ambiguity about the Greekness of Macedonians portraying them as a potential barbarian threat to Greece. The late 500 BC sophist Thrasymachus of Chalcedon wrote, "we Greeks are enslaved to the barbarian Archelaus"

Demosthenes says for Philip II "not only no Greek, nor related to the Greeks, but not even a barbarian from any place that can be named with honor, but a pestilent knave from Macedonia, whence it was never yet possible to buy a decent slave".

He also calls Meidias, an Athenian statesman, "barbarian" and in an event mentioned by Athenaeus, the Boeotians, the Thessalians and the Eleans were labeled "barbarians"

In the Histories Herodotus calls king Alexander I, a Hellēn who ruled over Macedonians. in his eighth book he groups several Greek tribes under "Macedonians" and others under "Dorians".

Thucydides distinguishes between three groups fighting in the Peloponnesian War: The Greeks (including Peloponnesians), the barbarian Illyrians and the Macedonians.

Isocrates defending Philip's Greek origins wrote, "...he understood that Greeks are not accustomed to submit themselves to monarchy whereas others are incapable of living their lives without domination of this sort ... for he alone of the Greeks deemed it fit to rule over an ethnically unrelated population"

Isocrates to Philip: "Therefore, since the others are so lacking in spirit, I think it is opportune for you to head the war against the King; and, while it is only natural for the other descendants of Heracles, and for men who are under the bonds of their polities and laws, to cleave fondly to that state in which they happen to dwell, it is your privilege, as one who has been blessed with untrammelled freedom, to consider all Hellas your fatherland, as did the founder of your race, and to be as ready to brave perils for her sake as for the things about which you are personally most concerned."

Philip named the federation of Greek states "The Hellenes" (i.e. Greeks), and the Macedonians were granted two seats in the exclusively Greek League in 346 BC.

With Philip's conquest of Greece, Greeks and Macedonians enjoyed privileges at the royal court, although Philip's armies were only ever led by Macedonians. The process of Greek and Macedonian syncretism culminated during the reign of Alexander the Great, who allowed Greeks to command his armies.

Aristotle advising Alexander "to have regard for the Greeks as for friends and kindred" and has also in his Politics refered to Macedonians as barbarians.

J. King, Carol “Allowing that there were living in ancient Macedonia throughout the Archaic, Classical, and Hellenistic periods people who were Greek, people who were akin to Greeks, and people who were not Greek, if one seeks historical truth about an ancient people who have left no definitive record, one may have to let go of the hope for a definitive answer. The ancient Greeks themselves differentiated between “Greeks” and “Macedonians...”

Now, who were the Barbarians at the time? What does DNA analysis say about Slavs on Balkan? Serbs have almost 1/3 of the Balkan origin gene which peaks in Herzegovina. It has originated in Balkan and spread out 7000 years ago and into other people now called Slavs (in Europe). However, it is not the most prevalent for the other Slavs - only certain South Slavs, like Serbs, Macedonians, Montenegrins, Bosniaks & Bosnian Serbs and Southern Croats.

History is like Playing the Hesse's Glass Bead Game with Pythagoras...

Learning from Egyptian stelae from Malta Jeremy Young, Marcel Marée, Caroline Cartwright and Andrew Middleton

In 1829, four Egyptian stelae dated 1,800 BC were found on Malta

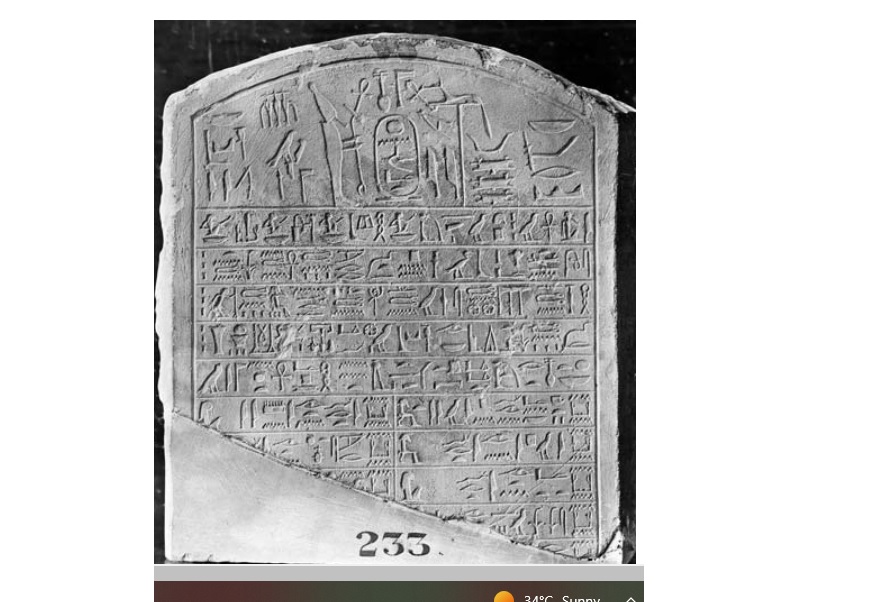

During the excavations for the foundations of the hospital in 1829, four Egyptian stelae came to light. They were excavated by Mr J.B. Collings, who sent them to the British Museum in 1836, where they have registration numbers EA 218, EA 233, EA 287 and EA 299.

"Based on their far-flung findspot, some have suggested that the stelae were locally made by Egyptian colonists who had settled on the island during the second millennium bc. This contribution argues that the stelae offer no basis for such historical reconstructions. Style, content and petrology demonstrate that all four stelae were made in Egypt and that they originally stood in the necropolis of Abydos in Upper Egypt. Microfossils show that these stelae are made of Egyptian limestones, which are of a different geological age to limestones available on Malta" Egyptian stelae from Malta.

The British Museum stelae suggest that each was destined to be set up in Abydos, the cult centre of the god Osiris. The stela EA 233, the British archaeologists tell us, principal inscription addresses ‘those living on earth, every wab priest, every lector priest, every scribe and every ka servant who may pass by this eternal stela’. Those reading tell all that they should recite an offering prayer for the benefit of all those commemorated on the monument. The version of the prayer inscribed on EA 233 invokes the king and ‘Osiris, lord of Abydos’

On EA 233, between the two deities, the living king is also represented – through a cartouche. This contains the thronename of Amenemhat III, who is said to be ‘beloved’ of both gods; his mention dates the stela to c.1855–1808 bc

Upper part of stela EA 233 from the Twelfth Dynasty, from the reign of Amenemhat III (1855–1808 BC) in British Museum

It has been suggested that the stelae came to Malta in Roman times or at some other point...

Read more

Learning from Lecture The Maltese and La Commedia Dell’Arte

Theatre is one of the oldest way of expression. It was at first a religious expression, meant to communicate with the Gods. A Scottish friend of mine Nicholas Jackman acted Macbeth, in the Shakespeare’s performance, at the Valletta’s Manuel Theatre this weekend. To be true to the play, at the time of our ancestors, the actors did believe in the witches they portrayed. To the audience, witches were a fact of life, real force manifestation, as real as the Hamlet’s ghost of his late father. That is why it is the most difficult to act a mad man.

In traditional societies the first shamans were our first actors. They improvised, channelling subconscious states. What psychologist Jung found in alchemy (transforming metal into gold) is a precursor guide to the psychology of humanity.

Read more